~ BÉNÉDICTINE ~

Herbal liqueur / 40% ABV / c.£30 for 700ml

Friends with: dark spirits, notably brandy, bourbon and rye. Italian vermouth. Absinthe. Peychaud’s bitters. Also, gin, French vermouth, sherry. And, cream, chocolate, coffee, etc.

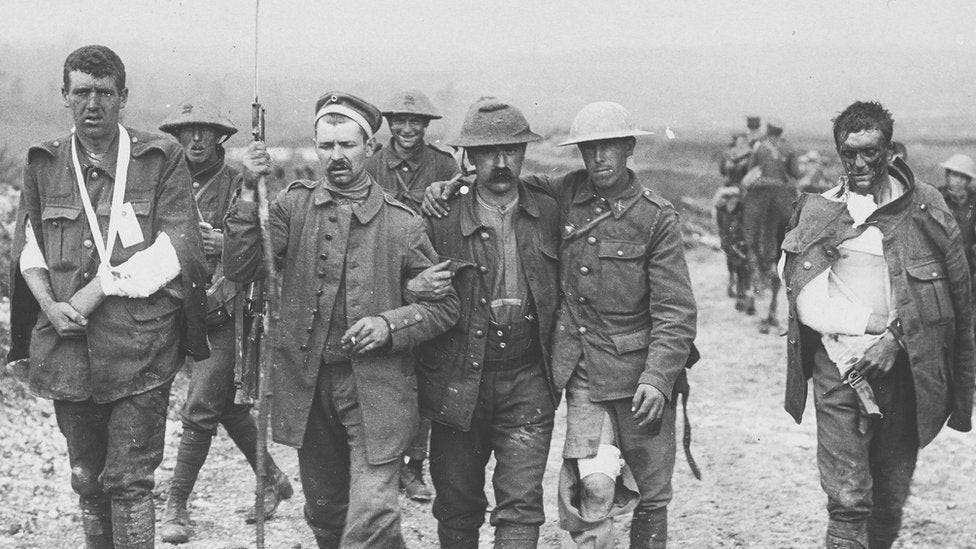

Imagine, you are a teenager in a northern English industrial town in 1914. The ruling classes of Europe have resolved to see how many of you they can annihilate in order to satisfy one of their most inscrutable codes of honour. The army turns up in the market square one day and the recruiting sergeant gives you a rousing blast of King and Country, valour and duty - the whole shooting match. Sounds fun. You sign up. And so do all of your friends. Only to discover that what you have signed up for is gas, schrapnel, mud, rats, blood, pain, madness - the “most colossal, murderous, mismanaged butchery that has ever taken place on earth”, as Hemingway had it.

One of the most famous stories of mass conscription in the First World War concerns the “Accrington Pals” - almost the entire cohort of young, fit and able men of that Lancashire town, who formed most of the 11th Batallion of the East Lancashire Regiment. This was to be the unlucky team that led the charge at Serre in the first Battle of the Somme in 1916, man after man, walking out of the trenches into the sights of the German machine gunners who couldn’t believe how dim the English were being - continuing to send men over the top after it was clear that the tactic was a disaster. But in the words of one English Brigadier-General:

“The lines which advanced in such admirable order, melted away under fire; yet not a man wavered, broke the ranks or attempted to go back. I have never seen, indeed could never have imagined such a magnificent display of gallantry, discipline and determination."

Out of 720 Accrington Pals, 584 didn’t make it back. We can be grateful for many things in 2023, but I think the fact we don’t regard the sight of hundreds of young men marching senselessly to their deaths as “magnificent” is probably one of them.

But OK, let’s imagine you’re one of the lucky ones. You’re from nearby Burnley. You’re in the 5th Battalion. You’re shot in the neck. You spend the night in a shell-hole, watching as rats begin work on the corpse of a guy who once went took your sister the cinema, listening to the rattles and pffts and blasts of death. But the stretcher-bearers find you in the mists of the morning and - cheer up, lad, you’re going to pull through. You are now recovering from your wounds in a hospital behind the lines in Fécamp, on the coast of Normandy, haunted and shattered. A French nurse, buttery and celestial, hands you a cup. It containeth Bénédictine, D.O.M., a liqueur made by the local monks as an act of silent devotion to the Lord. You put the cup to your lips and hallelujah! It is the sweet taste of salvation. Or as Private Archy Wilson wrote to his wife, Clementine:

"Our nurse brought round a very nice drink with hot water in it called Benedictine. It warmed my heart. Lads of the 5 E Lancs Batt’ are in my ward and they all drink it.”

Now: would you believe that to this day, the largest single consumer of Bénédictine D.O.M. is not some fancy Parisian hotel nor some hip New York speakeasy but The Burnley Miners Social Club? It’s true. Many thousands of East Lancashire men passed through Fécamp in the First World War and they brought back with them a taste for the local liqueur. Some of them apparently even had a Christmas party at the Palais Bénédictine in 1917. “Benny and Hot” is the preferred serve: quite simply 50ml of Bénédictine topped with 100ml hot water. (This is known as a foutinette in France). You can even get it at Turf Moor, the local football ground. “It’s an emotional thing,” said Burnley’s head of hospitality in this insightful FT piece. “It’s almost a rite of passage for a true Burnley supporter. Everyone remembers their first game at Turf Moor; everyone remembers their first Bene.”

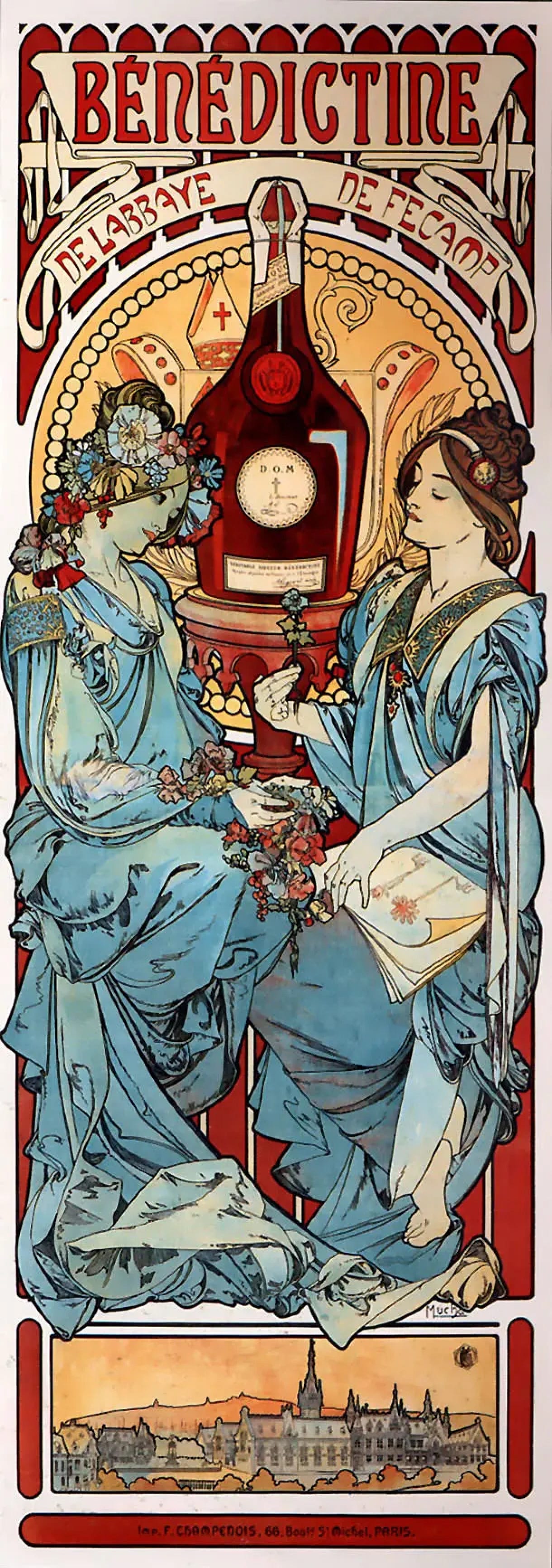

Taste Bénédictine and it really does seem like the liquid to warm the cockles of an exhausted Tommy. (Or, indeed, a Burnley supporter after a discouraging 5-2 home defeat). It is immediately comforting: metallic sugar, kingly spice, medicinal but in a nurturing, Mary Poppins sort of way, redolent of clean sheets, a warm fire, old friends and golden sickles. And it is a little celestial, too, having been made by Bénédictine monks - the silent type - since at least 1510 at the Abbey of Fécamp. I can imagine these monks in their cloister, hearing the shell fire, shaking their heads at one another and proceeding with their maceration. Whatever the opposite of war is, that’s what Bénédictine is tastes like.

So what is it? Well, neutral spirit, sweetened with sugar, and macerated and distilled with a secret blend of 27 herbs, roots and spices over a four-part process and then aged. That’s quite a process. And quite a recipe - the precise combination of herbs is (like its bar-mate, Chartreuse) a secret, known only to a mysterious “master herbalist” who for all we know, may be the Lord himself. Although it should be noted, in the interests of pedantry, that the modern Bénédictine recipe was actually formulated in 1863 by a Fécamp merchant named Alexandre le Grand.

Le Grand was apparently quite the entrepreneur - opening up the Palais Bénédictine as a tourist attraction, petitioning the pope himself for permission to use all the holy branding, and perpetuating the story that he had found the 1510 recipe amid the alchemical equipment in some dusty gothic attic - rather as Thomas Chatterton (below) claimed to have found his mediaval masterpieces in St Mary Redcliffe. And the story worked. Bénédictine soon found its way into all respectable establishments and many respectable cocktails, too. And for a dozen of these , you will have to read on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Spirits to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.